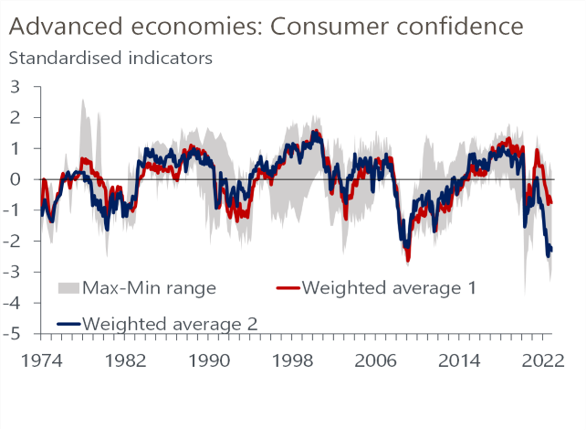

We’ve spent most of the summer discussing macroeconomic trends and data (from inflation to employment) that could change the course of policy and markets, so today we want to focus on a handful of catalysts between now and the end of the year that could have meaningful consequences for asset prices.

China 20th Party Congress

The 20th Party Congress begins on October 16, amid economic turmoil in the country largely driven by the property crisis and Zero-Covid policies.

What’s at stake?

It is widely believed that President Xi Jiping is aiming for a third consecutive (and likely life-long) term as President, bucking the trend of two-term limits established by law in the 1990s then reversed by constitutional amendment in 2018. On the real estate front, China has already begun to implement measures to provide relief to the troubled market and its developers by implementing a $29 billion loan program to help developers finish halted projects, relaxing home purchase restrictions, and lowering the mortgage rate for first-time homeowners in cities where selling prices continued to fall over the summer. With power consolidated post-Congress and a focus on Common Prosperity, we believe there is a chance of greater central government intervention in the market to assuage resident’s concerns about the sector and restart growth given the Chinese real estate market accounts for roughly 25% of the economy.

On September 30, Xi and other members of leadership attended National Day celebrations without wearing masks at one of their last public appearances before the Congress. This, along with Chinese MRNA vaccines being rolled out in Indonesia, could point to shift in Zero-Covid policies on the other side of the meeting. The last patient entered the 28-day EUA test for efficacy against current strains on August 29, and results are expected this month. With EUA approval of one or a handful of the 14 drugs that went to trial in November, we could see a full reopening of the country by April next year given the available vaccine manufacturing capacity.

What’s it means for markets?

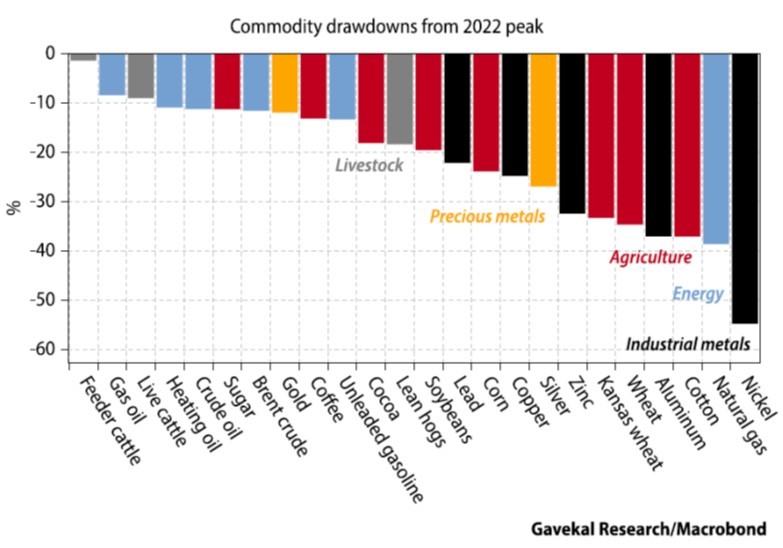

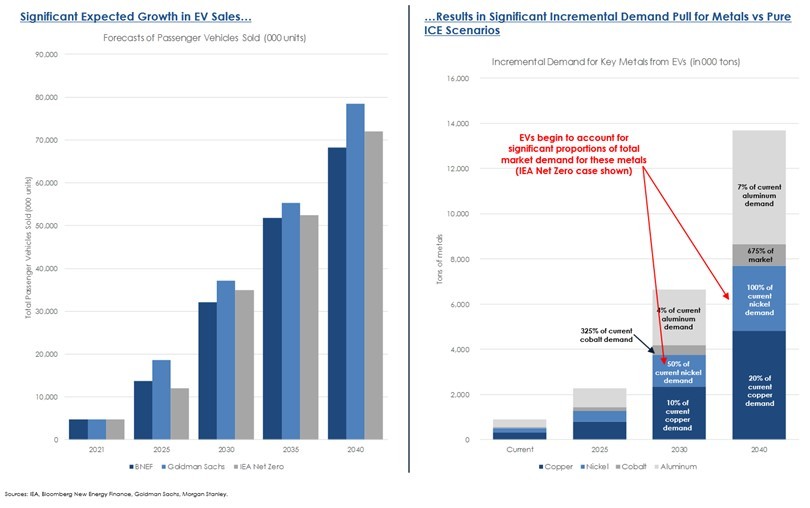

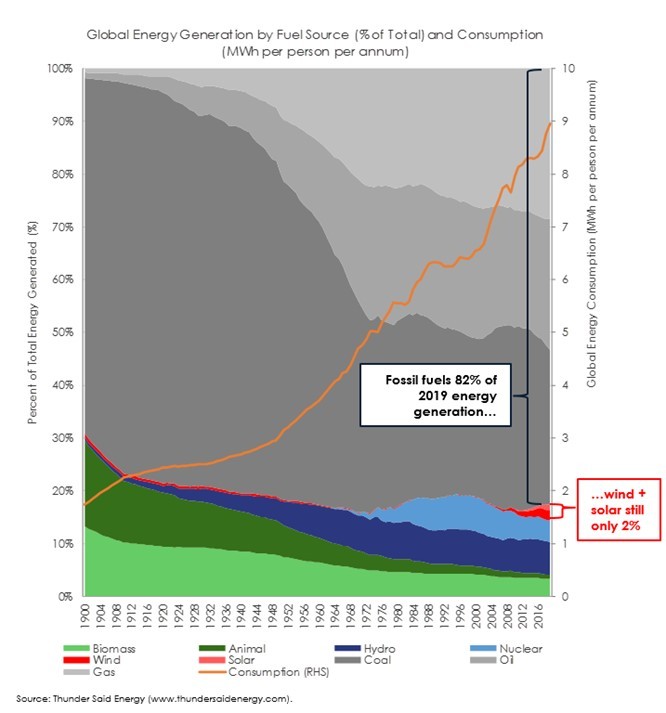

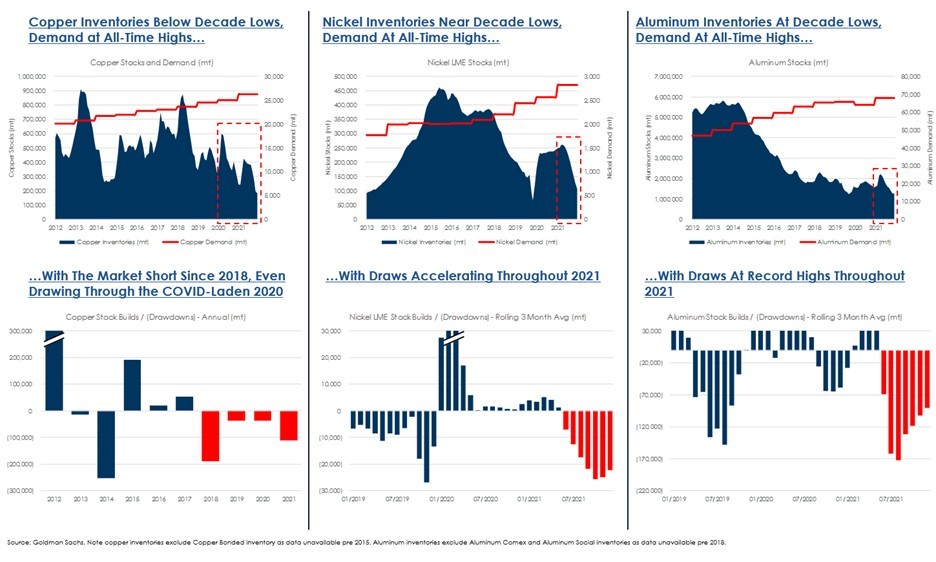

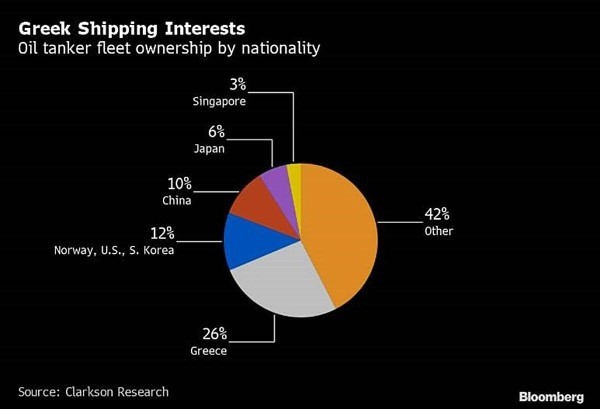

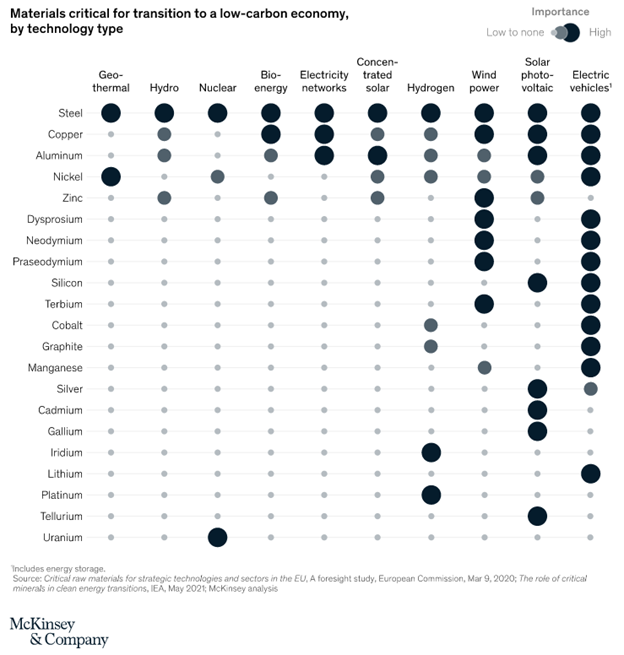

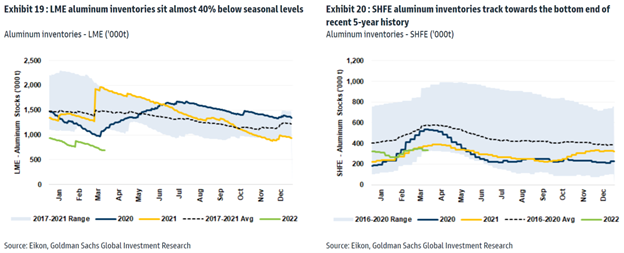

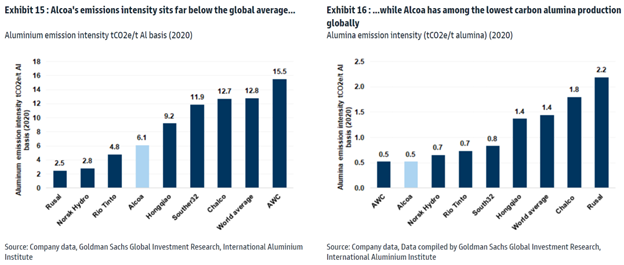

China is one of the largest consumers of commodities in the world. A reprieve on the property front would put a floor under building materials like steel, copper, and aluminum. A reversal of Zero-Covid rules and the reopening of the country would boost goods consumption, improve mobility, thereby increasing energy consumption, and increase non-residential fixed asset investment in sectors like renewable infrastructure. Altogether, these changes would represent a material change to the demand-side of many commodities from oil to cobalt, and re-rate prices in the sector higher.

Russia-Ukraine Escalation

This week, President Putin signed the decree approving the annexation of four Ukrainian regions (Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson), amounting to approximately 15% of the country’s area. Escalation in defense of “Russian territory” is a more significant risk than the market is pricing for the coming weeks and months as Ukraine continues its counter-offensive and other catalysts roll off the calendar. (Recall that Putin waited for the completion of the Beijing Winter Olympics to begin his “Special Military Operation.”)

What’s at stake?

Putin has ordered the Russian nationalization of Ukraine’s largest nuclear plant in Zaporizhzhia this week, and reports of Russian missiles hitting civilian and military targets in the region hit the newswire on Wednesday. Mounting counter-offensives from Ukraine across the territories could lead to further escalation by Russia. In the interest of defending land in the Russian Federation, the country’s articles of war or principles for engagement may allow for the use of more significant weapons against Ukrainian troops in the annexed areas.

NATO reported this week that Russia may be planning a major nuclear test near their border with Ukraine in the Black Sea, which the Kremlin has denied, but many news outlets reported the movement of nuclear weapon equipment by train toward Ukraine. We believe that the probability of a smaller tactical nuke being used in Ukraine, which has reportedly led to Kyiv distributing Potassium Iodide to its citizens, is being mispriced or at the very least, underappreciated in the market. Remember that the last nuclear test in the world occurred by the United States in 1992, and while the USSR conducted a test in 1990, the post-breakup Russian Federation has never performed one.

What it means for markets?

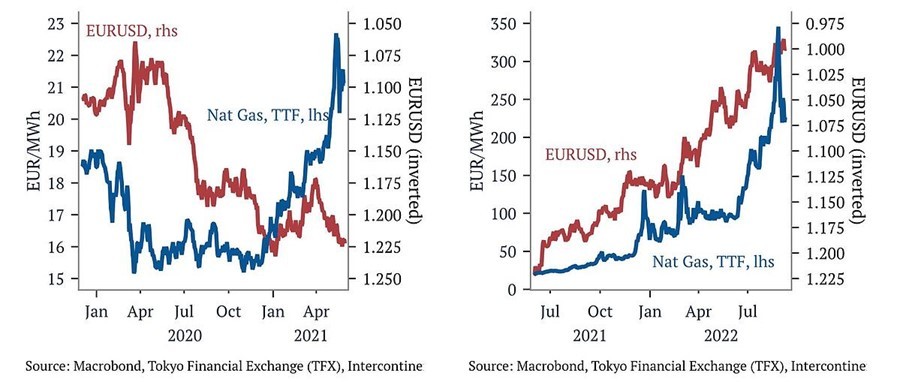

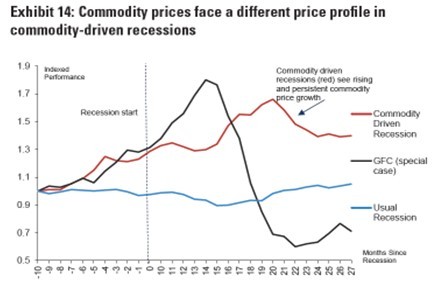

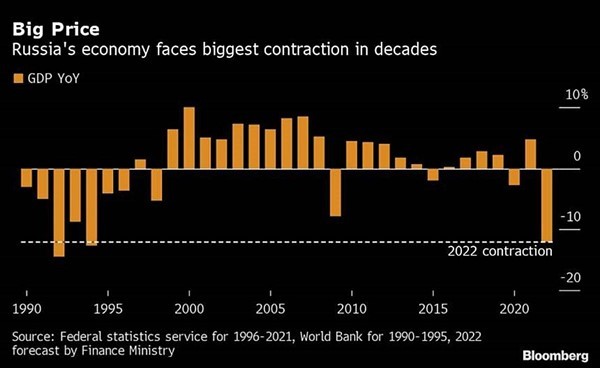

Significant geopolitical risk often begets a flight to safety – namely the US dollar and Treasuries – away from equities. Specific to this case, any nuclear attack by Russia would cripple relations between Russia and the West (and possibly the entire globe), resulting in less energy and metals making it out of the country, limiting supply, which would further weigh on economic output across the world, particularly in Europe.

Brazil Presidential Elections

In the first round of elections, former President Lula da Silva received 48.4% of the votes, in line with polls, while current President Jair Bolsonaro secured 43.2% of the vote, roughly 5% above polling numbers. The run-off election is scheduled for October 30.

What’s at stake?

Pro-Bolsonaro and right-leaning candidates did well in congressional races, gaining 22 seats in the House and guaranteeing his PL party would be the largest in both the House and Senate. Overall, the bi-cameral congress became less fragmented, but more polarized, which could make for a more oppositional congress in the event of a Lula win. We believe this result increases the probability of fiscal responsibility, regardless the result of the presidential race.

What it means for markets?

Given the increased probability of fiscal responsibility from both sides, we believe that once election risk passes and the final result is accepted by both the parties and general public, risk assets in the country should do well in the coming months.

US Midterms

Amid poor presidential approval ratings, United States midterms elections are slated to take place November 8 as a quasi-referendum on Biden’s presidency.

What’s at stake?

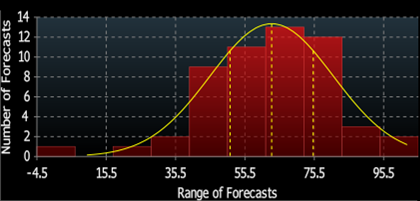

In the House, all 435 seats are up for re-election as they are every two years. FiveThirtyEight currently estimates that Republicans have a 70% chance of winning a majority in the House of Representatives, shifting control from Democrats and Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi.

In the Senate, 34 seats are on the ballot this year, with 15 currently held by Republicans, 13 by Democrats, and six seats open after senators announced they would not be seeking re-election. The current split of 50-50 slightly tilts to the Democrats, with Vice President Kamala Harris serving as the tie-breaking vote, and FiveThirtyEight currently gives Democrats a 2-in-3 chance of holding the senate, with an average number of 51 seats.

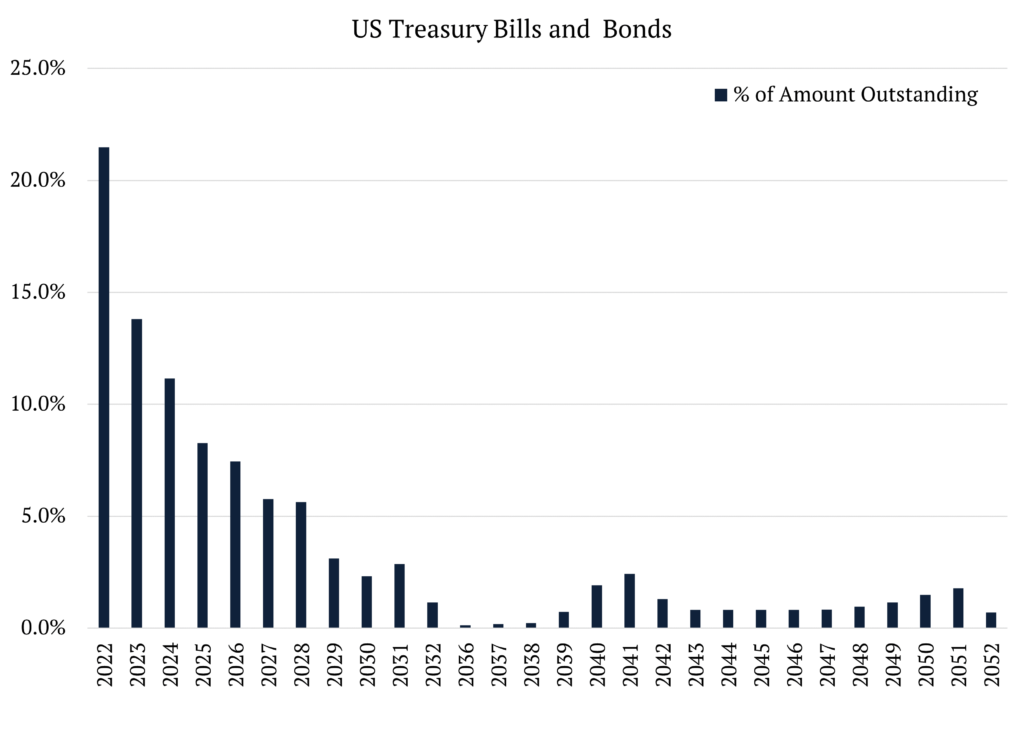

A split Congress often leads to gridlock, meaning Democrats would look to maximize use of the post-election lame duck period to push an expansive agenda while they still controlled both chambers.

What it means for markets?

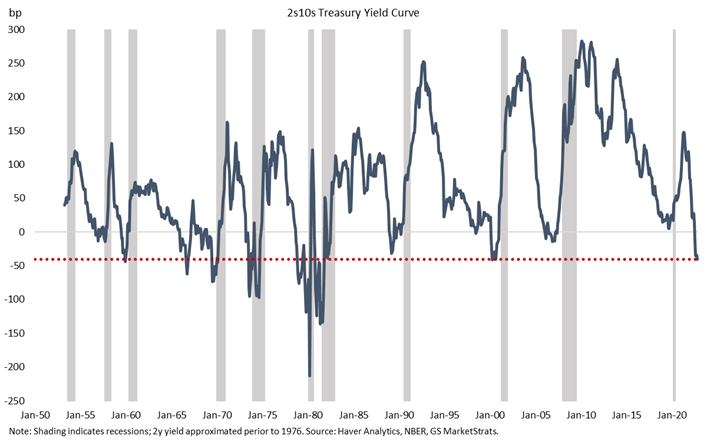

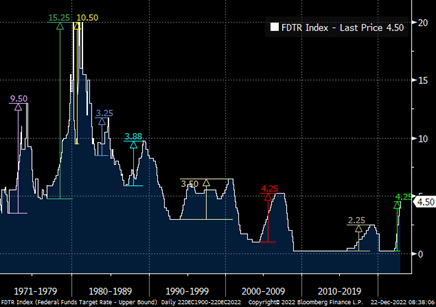

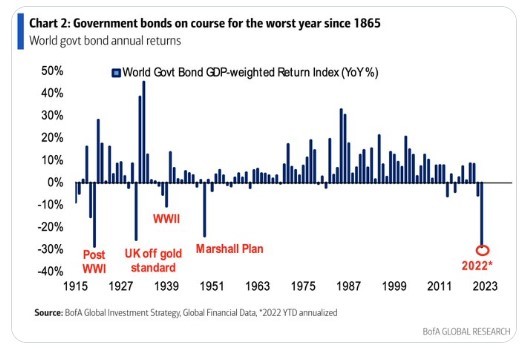

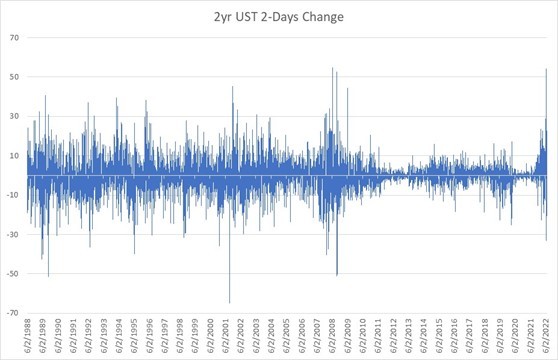

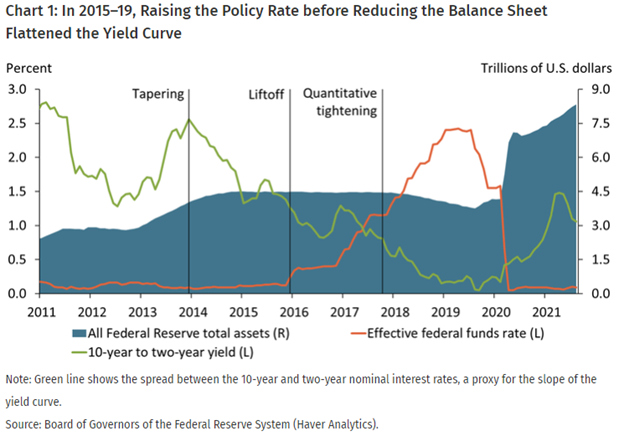

Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel noted to CNBC that markets tend to perform well when there is political “gridlock”. Since 1944, the S&P has averaged a 13% annual return in calendar years with a Democrat president and split Congress. More immediately this fall, the debt ceiling debate, the potential for more fiscal spending toward monkeypox and hurricane aid among other things, and the possibility of more SPR releases to dampen inflation effects for a voter-base most energized by the economy have the potential to impact Treasury markets and oil markets, with a derivative impact on equity prices. Finally, while the Fed maintains an apolitical stance, a deluge of inflationary fiscal measures could influence its interest rate path, which could weigh on all asset classes.

OPEC+ Meeting & Further SPR Releases

After announcing 2mbpd cuts to quotas on Wednesday, which will amount to roughly 900k bpd of less production by OPEC+ members after accounting for missed quotas, the cartel announced that the current production agreement would be extended to the end of 2023 and that they would be meeting every two months in lieu of the current pace of monthly meetings. In response, the White House said that Biden would continue SPR releases as appropriate, with reports of another 10 million barrels being released in November to combat rising gas prices, again.

What’s at stake?

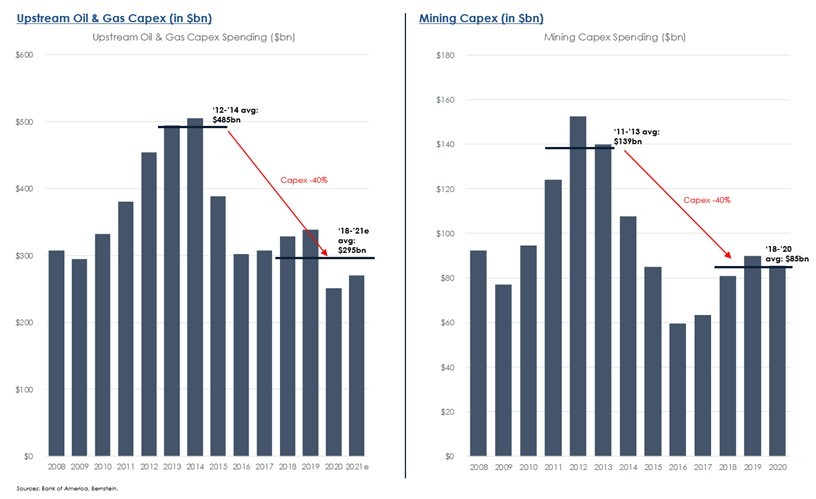

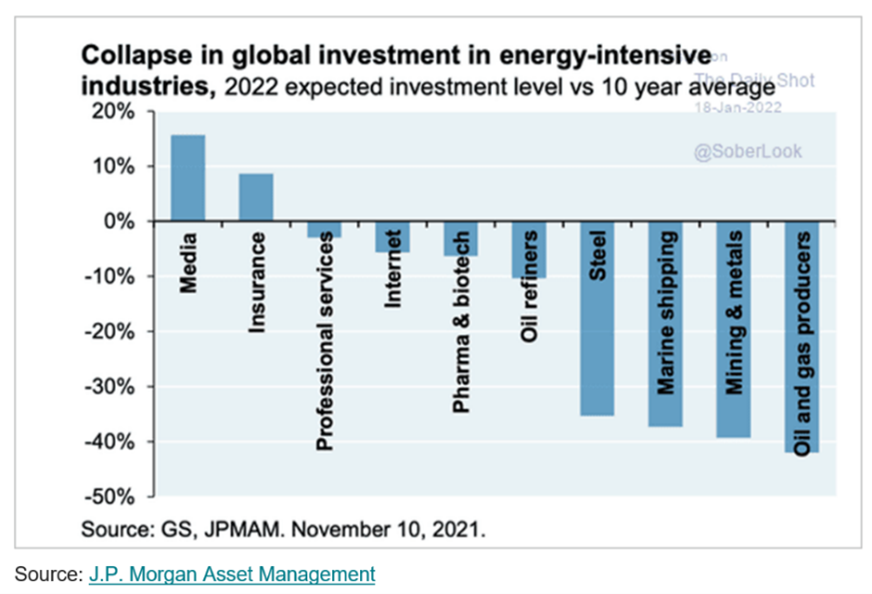

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is at its lowest levels since 1984, with the population of the United States approximately 45% higher, and the Biden administration has leased the fewest number of federal acres for energy production through 19 months in office since Harry Truman in 1945-46, when offshore drilling was new and the federal government didn’t control deep-water leases that make up the largest part of the federal oil-and-gas program today. OPEC+, citing a potential global slowdown and less directly, a dissatisfaction with the price of oil, opted to decrease production as the US has either intentionally or unintentionally massaged prices lower through oil releases. Most of the actual production cuts will come from Saudi Arabia, and interestingly enough, Business Insider reported on Thursday that the kingdom had lowered oil prices for Europe but raised them for the United States. The administration appears to be gambling that SPR releases will help their prospects in the midterm elections, while at the same time playing chicken with OPEC+ on production, decreasing the country’s ability to manage in the event of any positive oil demand shock.

What it means for markets?

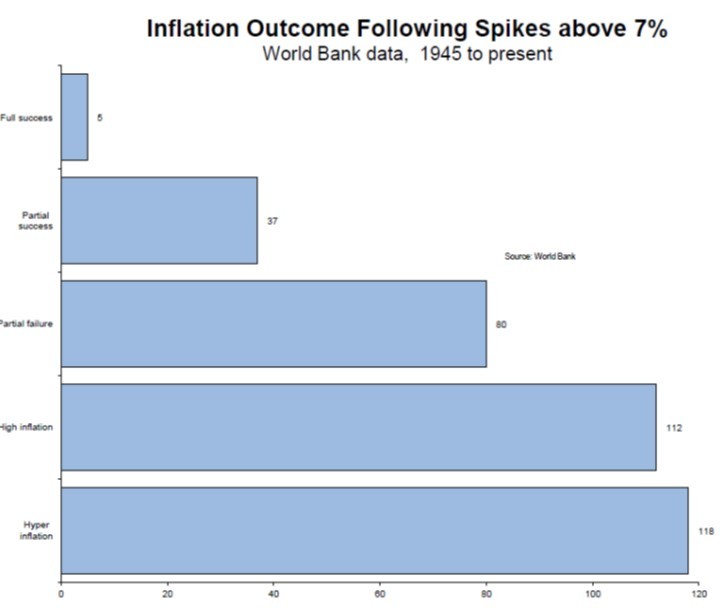

With interest rates marching higher increasing the cost of capital and the green lobby in DC targeting oil and gas companies, domestic producers have not been quick to bring more wells back online. Any rebound in Chinese demand, or a ban on domestic exports, could result in a significant increase in the price of energy at a time when domestic production is lacking and disincentivized from growing. Energy prices are a natural pass-through to virtually everything, raising the floor on commodity prices and potentially re-accelerating inflation which could possibly lead to more hawkish monetary policy in the US. Such a move would not only weigh on equity prices, but also be a tailwind to the US dollar in the event that other central banks have less latitude to tighten. Further tightening by other central banks, namely the ECB, could push those countries deeper into recession and further weigh on both global growth and markets.