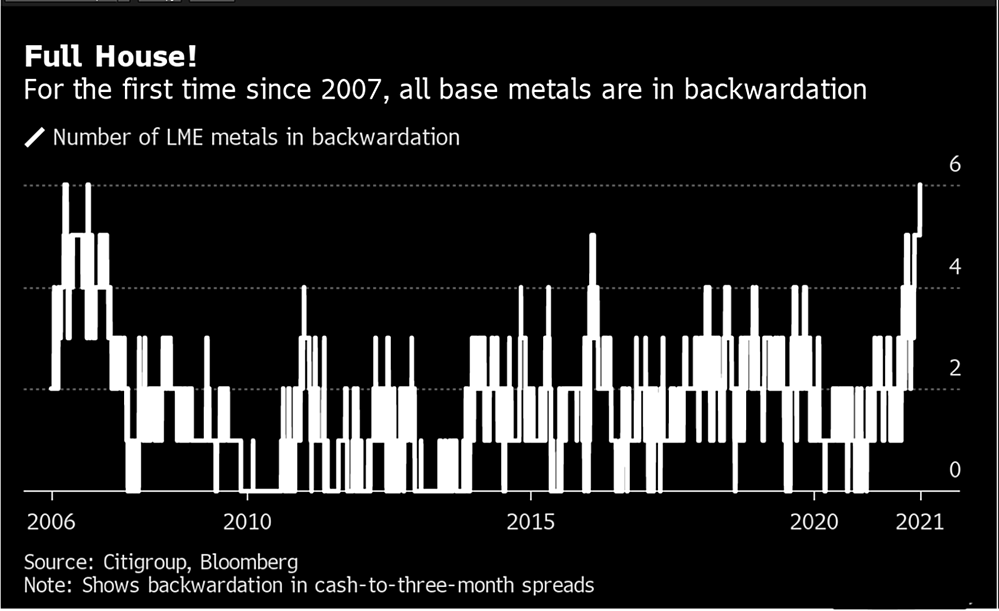

A quick note on commodities… Historically tight inventories have led to all six base metals (Aluminum, Copper, Nickel, Lead, Tin, Zinc) listed on the London Metals Exchange to trade in backwardation for the first time since 2007.

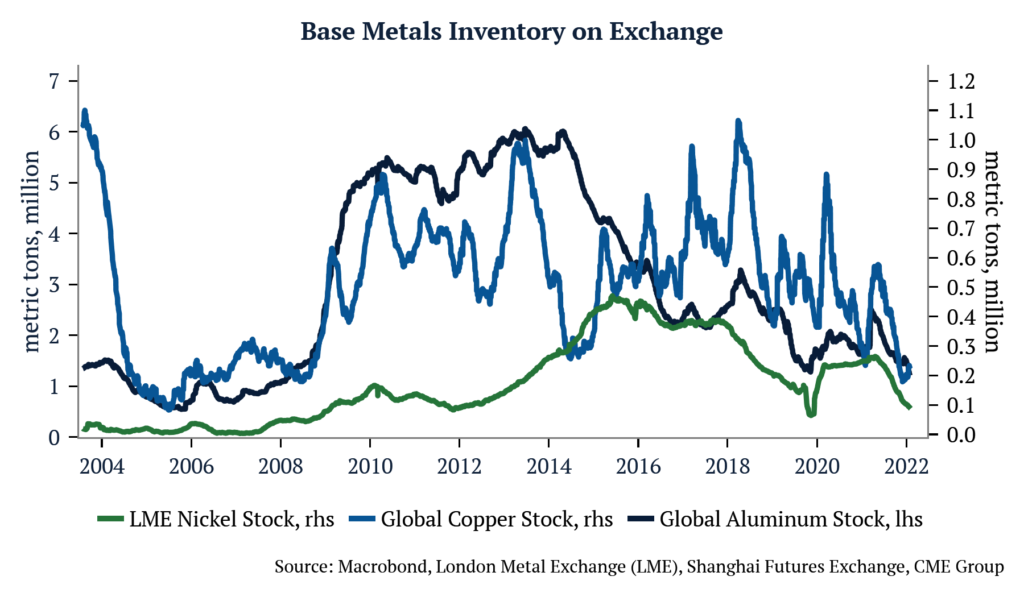

Of those six, some of the tightest markets are in Aluminum, Copper and, especially, Nickel, which has the largest deficit in its history. Using the average daily production of each metal and aggregate inventories across Shanghai, London, and United States metal exchanges, we estimate global aluminum inventories to be approximately 5.8 days of production, copper at 2.2 days of production, and nickel at just under 13 days of production. Actual daily draws from exchange are variable, but this illustration speaks to the level of tightness in the market.

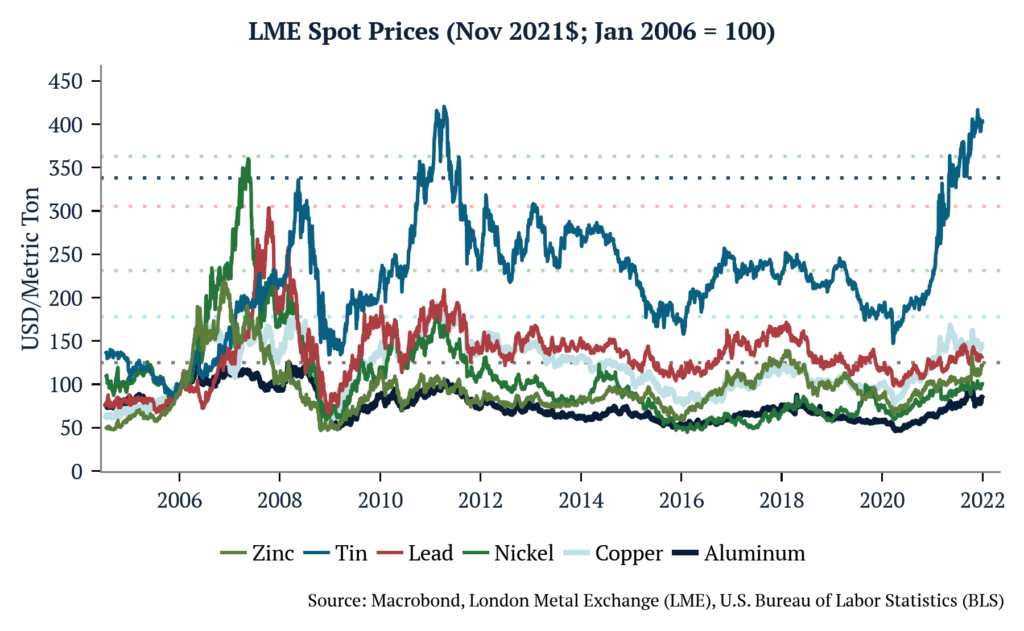

All but tin have upside to the levels reached in the last period of backwardation across the sector, after adjusting metal prices for inflation.

Bear in mind that while the price run-up in 2007 was also the result of a supply shock, albeit for different reasons, there was a sharp decline in demand caused by the bursting of the housing bubble and onset of the Great Financial Crisis, just as more supply began to come to market. The setup this time appears to be different. Persistent underinvestment in commodity extraction over the past decade, coupled with increased demand driven by government net-zero goals rather than private industry (e.g., homebuilders), suggest that this rally could be much tighter for much longer. With EV penetration increasing around the world, including in China, where nearly 20% of new car sales are electric, and the fact that those vehicles require between 5-6x more metal than internal combustion engines, we could see pressures drive prices past 2007 levels.