Divestment, the act of removing and or excluding particular sectors or segments of the market from investment portfolios, was all the rage at the beginning of the last decade in the face of climate change. Based on my perspective, however, the results of such action by institutions and portfolio managers have been uninspiring.

For citizens of a democracy, voting is the most important action one can take toward shaping the future path of economic and social policy in his or her municipalities, states and nations. George Nathan, an American editor in the early- to mid-1900s, has been credited with saying, “Bad officials are elected by good citizens who do not vote.”

A case can be made that the same level of responsibility held by voters in a democracy sits with the market when it comes to shaping a company’s business decisions. Shareholders, irrespective of size, are typically entitled “to vote in elections for the board of directors and on proposed operational alterations such as shifts of corporate aims and goals or fundamental structural changes,” according to Investopedia. When you consider the democratic tradition of voting to make a change, particularly in American culture, it is hard to “square the circle” when it comes to supporting divestment.

However, recently, the trend seems to be shifting. This year, shortly before Memorial Day, the board at Exxon “conceded defeat” to impact investment firm Engine No. 1, which drummed up (and won) a proxy fight by alleging the company was being disingenuous with its emissions targets and not taking its impact on climate change seriously enough. Through a combination of publicity and engaging with large shareholders, the newly launched firm used activism to, against the recommendation of Exxon’s executives, elect three candidates to the company’s board who are committed to pushing the company’s business model away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy.

As an investor, one should strive to understand as many of the components of risk that will impact a company’s (or country’s) future rate of growth and ability to operate efficiently. We founded Norbury Partners, a sustainable macro fund, on the premise that it is impossible to make informed investment decisions without considering changing consumer preferences, as well as changes in the regulatory and policy environment arising from climate change mitigation and adaptation and access to basic services. However broad, certain sustainability information can be material to better understand macroeconomic variables and the idiosyncratic risks associated with countries and the future cash flows of corporations.

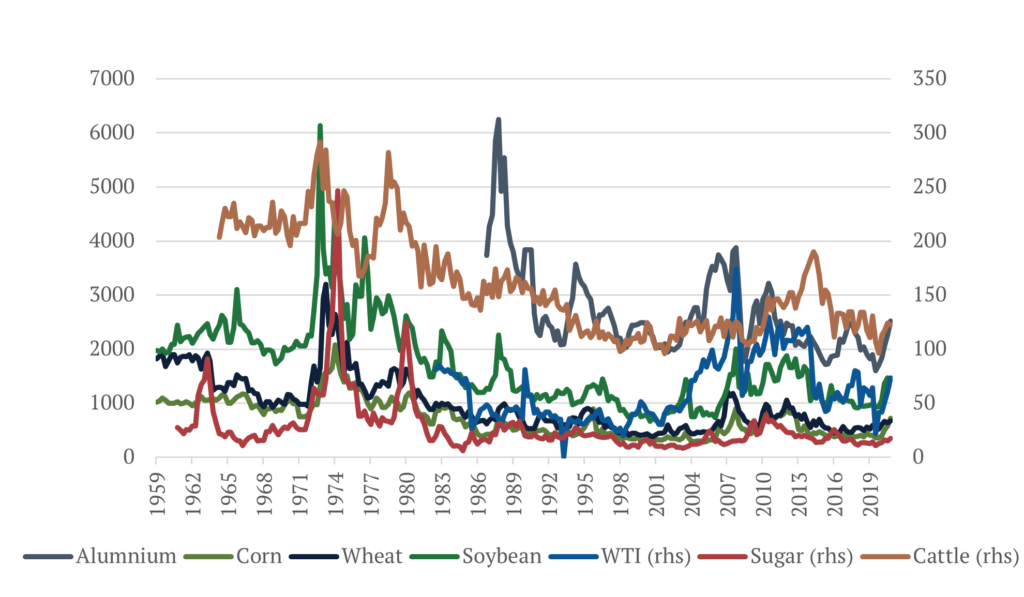

From severe flooding in low-lying cities caused by mega-storms to drought-stricken commodity harvests, and everything in between, it has become increasingly clear that fundamental data found on company 10-Ks, or in periodic sovereign data, does not always wholly paint a picture of the future. Like people and their voting habits, companies and countries change with the times. Look at the past six months: the United States rejoined the Paris Climate Agreement and the largest economies in the world committed to net-zero targets within the next 40 years.

Rather than divest, rational investors seeking to maximize their returns should look for companies in the early or interim stages of change that will create outsized value in a changing world energy paradigm. Often by the time companies mature, becoming renowned for their sustainability practices and stalwarts in environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG)-focused portfolios, the excess value created when a company managed its downsides and built upside has already been priced into the stock.

Furthermore, what industry is going to see a more significant shift in the changing world paradigm? Someone will have to provide the innovation and energy required to power a growing, more technology-centric world. By participating in a company that has long been called for divestment, Engine No. 1 has demonstrated that investors have a better chance of shaping the future and capturing upside for themselves as active shareholders than they do as spectators in the market.

Finally, the nature of markets guarantees that by divesting, particularly on a large scale, prices will be pushed down with more sellers than buyers. This, in turn, increases the expected return for divested company shares where business will continue as usual, bringing non-ESG-focused investors into the fold who are less likely to make the required changes (or vote along those lines) for a sustainable future.

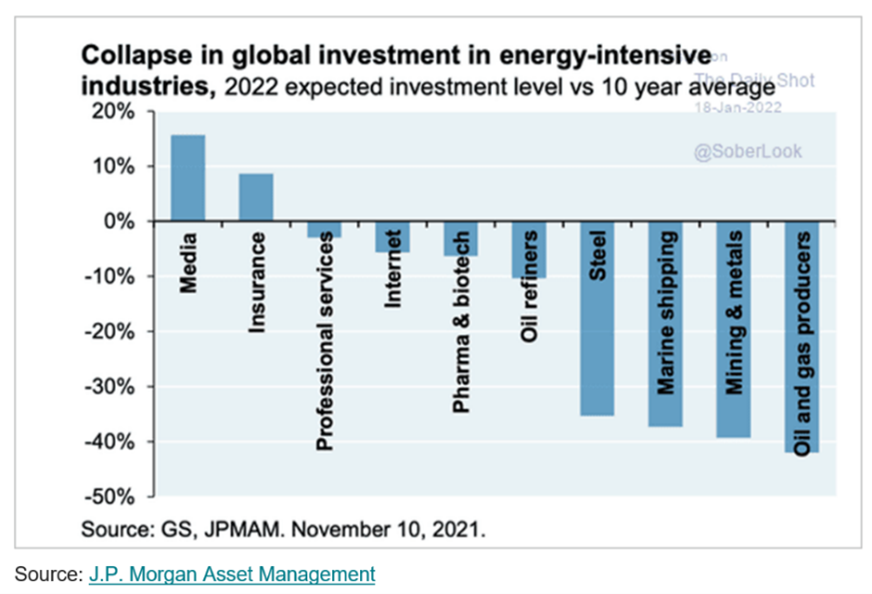

By last fall, more than 1,200 institutional investors, with more than $14 trillion in assets, had made commitments to the divestment of fossil fuel holdings. Yet, the way I see it, the movement has failed to bring about the change it has been lauded to produce.

As citizens of a democracy, it is our right and our duty to exercise our vote in order to institute change. As investors, we should be looking for the upside to be found in energy companies transitioning to technologies more suitable for the future that policymakers have committed to. And as students of markets, we must recognize that by divesting shares and pushing prices down, we increase a stock’s expected return, thereby inviting marginal investors less committed to ESG and a sustainable future as shareholders, and creating a feedback loop of “more of the same,” with little prospects of advancing toward our goal.

Voting should not be something we talk about every four years. Utilize your ability to be an active market participant to drive the change you want to see.

Article also submitted to Forbes