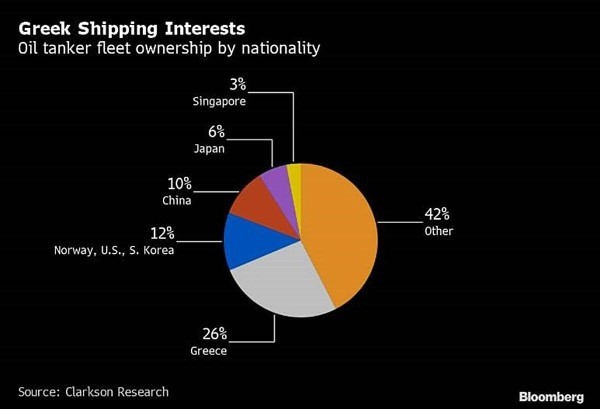

Last week, the European Union announced plans to ban Russian crude oil over the next six months and refined fuels by the end of the year as part of the sixth round of sanctions. Over the weekend, the proposed ban on its vessels transporting Russian oil to third-party countries was dropped, but the EU will retain a plan to prohibit insuring those shipments. Bloomberg reports that about 95% of the world’s tanker liability cover is arranged through a London-based organization that must heed European law. Without such insurance, Russia and its customers would have to find alternatives for risks, including oil spills and mishaps at sea, that can quickly run into multi-billion-dollar claims. (For more on the commodity trading business and how insurance impacts commodity flows, listen to “Javier Blas Explains How Commodity Trading Shops Really Work” on the Odd Lots Podcast).

The pain to European consumers is clear. The region last year got 27% of its oil imports and approximately 40% of gas from Russia (paying $104 billion for supplies of fossil fuels). Economists estimate a full embargo on Russian oil and gas reduces the area activity from 4% (Barclays) to 2% (Bundesbank), while some analysts have argued that the impact would be lower than that. Germany’s vice-chancellor Robert Habeck said his nation has already cut its reliance enough to make at least a full oil embargo manageable with the share of Russian crude in German imports falling to about 12% since the invasion.

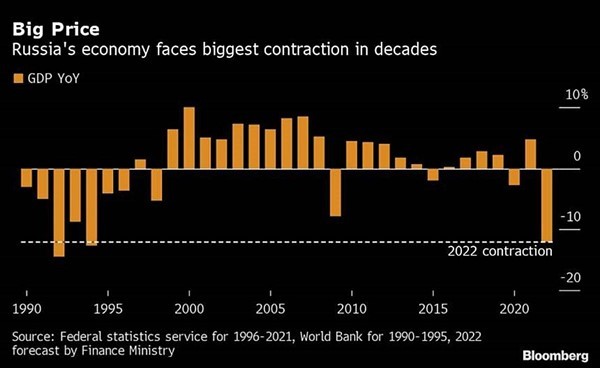

For Russia, an oil embargo would limit the inflow of foreign currency and make difficult spending cuts necessary. Russia’s Finance Ministry expects its GDP to shrink as much as 12% this year, on par with the turmoil seen in the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union ultimately dissolved. On Monday, Russia said it expects its oil production to rise in May, and that it is seeing new buyers for its crude, including in Asia. But how much of this is true and how much of it is just posturing?

Changing oil shipping routes from Europe to Asia is not as trivial as Russia would lead us to believe. Different vessels are required to efficiently transport oil on different sea routes. When done properly, transport of crude oil by tankers is second only to pipelines in terms of efficiency, with the average cost of transport at $0.02 to $0.03 per gallon. When transporting oil, there are three main types of vessels: Very Large Crude Carriers / Ultra Large Crude Carriers, Suezmax, and Aframax vessels. There are about 800 VLCCs/ULCCs in the world used for long-haul routes and they carry around 2 million barrels each. There are about 700 Suezmax vessels capable of passing through the Suez Canal in a laden condition, and they can carry around 1 million barrels on long-haul routes. Lastly, there are about 600 Aframax carriers in the world, known as “go-fast boats,” moving about 600,000 barrels on short-haul routes.

Zoltan Pozsar of Credit Suisse estimates that roughly 1.3 million barrels of oil get shipped from Primorsk and Ust Luga to Europe on Aframax carriers and these journeys take a week or two to complete. Russia does not have pipelines to Asia so the only way to sell its product to new buyers is by using sea routes. However, it is uneconomical to transport crude on long-haul voyages on Aframax carriers and they would need more VLCCs/ULCCs to make that happen. Because Russian ports are not deep enough to dock VLCCs/ULCCs, they would first need to use Aframax vessels to get to a port to then transfer the crude to larger vessels. This transfer itself can takes weeks. After the transfer, the larger vessel would then take about 70 days to get to Asia, unload, and take a similar amount of time to return. This compares with just a couple of weeks when shipping to Europe. This would cause a sharp slowdown in Russia’s economic activity. The world would also need an extra 80 VLCCs/ULCCs to accommodate that change which represents 10% of the current global capacity of those vessels. Additionally, this only accounts for the re-routing of one product, oil, but Russia exports every major commodity.

The increasing competition for selling oil in Asia would have an impact on one of the Middle East’s biggest consumers. It is then no surprise that Saudi Arabia cut oil prices for Asia buyers over the weekend. This will not make Russia’s situation any easier. China benefits when Russia becomes weaker and more isolated and hence more dependent on Chinese goodwill. Let’s not forget that during Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014, China got Russia to agree to build (and possibly pay for) a dedicated pipeline at lower prices than it sells to Germany, even when the cost of gas from the new field is higher.

The cost of banning Russian oil might be large for Europe, but it can be even larger for Russia. This should increase the impact of sanctions and diminish the possibility of a unilateral cut in supply in the near future.